Henri Matisse, 1890, Still Life with Books and Candle, oil on canvas, Realism

I’ve been making reading plans for 2026 based on what I learned last year. The biggest revelation was slow reading is enjoyable reading. I also rediscovered the classics are really good books.

- I’m in a bookclub and I plan to read the monthly selection. The bookclub attenders range in age from young mothers to grandmothers. The choices here are often different than I would naturally gravitate toward, and I love that. We aim for a book a month but average about seven a year.

- Read Your Bookshelf Challenge by Chantelle Reads All Day. (It’s not too late to join if you would like to make progress on your TBR shelf.) I have a basket of unread books that were at one time an impulsive mood choice and then I didn’t get to them. This basket is overflowing and the goal is to reduce the number. This challenge has a monthly prompt to help choose the next book. And the book needs to be one you own but haven’t read. I’ve also put a buying freeze on myself. It’s painful to say, but seems necessary.

- And I will continue to read classics slowly. I plan to take small breaks in between and I have no idea how many, but it doesn’t matter because it’s about enjoying the journey.

- If a book fits more than one of these categories, I count it for both.

- Hopefully the books I read will be worthy of a review here. I plan to simplify my book ratings but haven’t settled on just how to do that. I have a simple three-star approach in my book journal and am trying to come up with a variation to use on the blog. And I’ve adopted two phrases that help me classify them: Book love- couldn’t put it down; Book respect- can’t stop thinking about it afterward.

Bookclub: The Q

The Q by Beth Brower, 2021, 477 pages

Quincy is the brilliant mind behind The Q, a wildly successful newspaper made entirely of questions.

But The Q also controls Quincy. Her obsession with every detail at the printing house prevents her from building relationships, facing her own emotions or even taking basic care of herself. Aside from her impeccable, masculine suits, that is.

Her Uncle Ezekiel has a plan that goes into effect with his death on the eve of the new year of 1898. In the next twelve month, Quincy must fulfill every requirement in her uncle’s will or she loses The Q. Ezekiel appointed Mr. Arch as solicitor of his will and he must not tell Quincy the requirements nor help her in any way. Quincy in turn is not allowed to fire Arch without forfeiting her rights to The Q.

I expected this to be a typical romance, but there are several ways where it isn’t. It’s long and complicated enough to develop nuanced and realistic characters. She was mean! Snarky humor and sarcastic reparte that endured through the whole book. Not a lot of warm and cozy feelings.

It had some elements of classic- I had to wonder what it would be like with a current setting and a few monologues on social issues or injustices. I got bored part way through, which is typical of many classics. By the end, I had the urge to start at the beginning, because I was sure I missed some interesting connections. Maybe those aren’t exactly scholarly observations; I’m an ametuer classic reader, after all. If you compare it to Pride and Prejudice, Quincy has both faults in generous portions.

There was just enough room in the carriage for two reasonably sized egos.

-pg. 148

Throughout the book, Quincy is avoiding, or struggling to process, trauma from her childhood. I had to wonder if her feelings, reactions and emotions translate to real people? If they do, reading this could be a way to understand yourself or those you love who are walking through trauma.

The Q by Beth Brower is a highly discussable book. Our bookclub talked about it for nearly two hours.

Extra: Recently I heard several people mention how they were enjoying The Unselected Journals of Emma M. Lion, also by Beth Brower. I read the first one and thought hmmm… So I tried the second, and now I don’t want to put it down. I might finish today!

Emma M. Lion is a spunky Victorian young lady denied her living by a self-serving relative who buys morning cloaks with the money that rightfully belongs to her. In her journal she tells it like it is, or maybe she’s unreliable, I’m not sure yet.

There are at least 8 volumes of Unselected Journals published and the author is working on more. I would describe them as feel good books with a dash of L. M. Montgomery sweetness and spunk.

And I do wish I lived on Whereabouts Lane.

RYBS: A Schoolteacher in Old Alaska

A Schoolteacher in Old Alaska by Hannah Breece, 1995, 270 pages

Hannah Breece, a proper middle-aged woman, braved the Alaska frontier in the early 1900’s to teach native children. Alaska at this time was a territory of the United States, and was full of prospectors, gold diggers, unscrupulous and honest white people and Indians Braving the weather, terrain, and wild animals was only part of the adventure. Hannah also braved prejudice, indifference and years of superstition to bring reading and writing to Alaska’s native children. And Miss Breece did not stop with helping children. She taught the mothers how to cook, often in the same room as the children learned. She brought seeds and fabric and taught gardening and sewing. On Sunday, she taught a Sunday school. Hannah was a force to be reckoned with.

Hannah spent about seven years in Alaska, starting when she was 45 years old and working under the authority (sort of) of the United States Educational Policay and Sheldon Jackson. She spent time in at least four communities, with very different experiences and results. Her memoir is very proper, she had hoped for it to be published during her lifetime and likely didn’t want to slander acquaintances. Futher explanations by the editor fill in the gaps about what life was really like.

This book is Hannah Breece’s memoirs, gathered from her correspondence and journals, and edited by her great-niece, Jane Jacobs.

Hannah Breece has my respect!

To be openly proper and conventional yet also openly daring is a way of being that was seldom available to women of the past. Some who did pull off this trick without being either aristocratic or rich were Americans on the frontier. Hannah Breece was one of these women. –First lines of A Schoolteacher in Old Alaska

Classic: Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, 1866, 472 closely typed pages or nearly 20 hours on audio. Translated from Russian to English by Constance Garnet.

I finished this book yesterday. It may be premature to try to write a review today; this book deserves some thought.

Tristan from the Classics says: (paraphrased slightly by me) To understand Crime and Punishment we need to understand Fyodor Dostoevsky himself. Born in 1821 in Moscow, he lost both his parents at an early age and was sent to a strict military academy. This was tragedy enough, but Doesoevsky’s life took a darker turn when he became involved with a group of radical intellectuals who were influenced by Western European rationalism and socialism. In 1849 he was arrested for his involvement with this group and sentenced to death. At the last moment his sentence was changed to exile and hard labor in Siberia. This near death experience followed by years of suffering profoundly influenced his world view. It was during his time in Siberia that Doestoevsky rediscovered his faith in Christianity. The tension between rationalism he had once embraced and the Christian values he returned to is at the heart of Crime and Punishment.

Crime and Punishment was printed in 1866 at a time when Russia was grappling with rapid social change. It was well-recieved and recognized as a powerful work exploring human nature and morality, and the labyrinthine passages of the guilty mind.

The main character, Rodyon Romanovich Raskolnikov, is a young law student in St. Petersburg. He falls upon hard times and cannot pay the rent for his small garret room so he avoids meeting the land lady. He abandons his studies, stays cooped up in his coffin-like room and refuses to eat.

An idea was pecking at his brain like a chick in an egg.

This thought was that some men are superior to others and are not to be bound by the laws that govern lesser men. Raskolnikov thinks much of Napoleon and wonders if maybe he is a Napoleon himself. He hatches the plan to rid the world of the pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna, (she is ugly, old, a cheat, a ‘louse’ on society) and use her money to do good, namely to relieve his own and his mother and sister’s poverty.

Raskolnikov successfully pulls off the crime.

Alas! He has a conscience.

Though no evidence or suspect lands on him from city officials, his inner anguish punishes him night and day. He gives some money to a woman he doesn’t know to pay for a funeral for a man he had met only once. He hides the rest of the loot and never retrieves it. Razumikhin, a fellow classmate and friend, tries to help him but he has no idea of all that is going on in Raskolnikov’s mind. Raskolnikov’s mother and sister come to St. Petersburg to help support him but they cannot relieve his suffering. The irreconcilable dualism of Raskolnikov’s character, his pride and superiority on one hand and gentle kindness on the other, refuse to let him rest.

It is left to Sonia, a poor girl rich in faith, to point Raskolnikov in the right direction.

This story will convince you that morals are absolute. The end does not justify the means. Live humbly. Life is sacred.

I listened to Crime and Punishment on Librivox. Expatriot, the reader, did an excellent job. Porfiry’s laugh and Katerina’s tuberculosis cough added chill factors. Don’t let all the Russian names discourage you. Raskolnikov is not a likable character, yet I found myself rooting for him when he finally does the right thing.

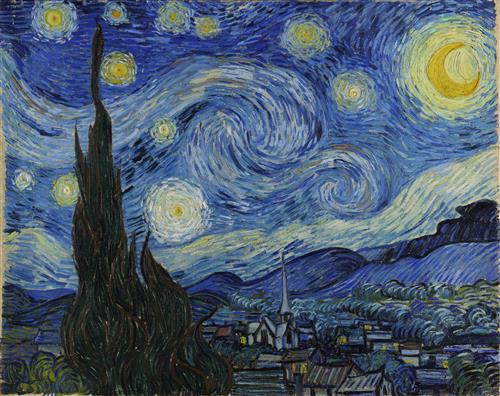

Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, oil on canvas, Impressionist style, 1889

One response to “What I Read in January”

Yay, the library can get Hannah’s story! Thanks!